By: Brian Warner

In her review of the 2019 remake of Child’s Play, Ruth Eshuis writes that it

is a story built on wicked foundations and may only be enjoyable to those who take pleasure in evil . . . There are dark and heavy themes relating to death, abandonment, shallow friendships, bullying, guilt, and anger which may cause [people] to feel sickened, depressed and confused. Relief, solutions, and justice are sadly missing. Overall, it’s nightmare material with little value.

Yikes.

While I haven’t seen Child’s Play, and thus can’t debate or defend her review (or confirm if I do, indeed, take pleasure in evil), there’s something about Eshuis’ reaction that sticks out to me. It’s not that it seems so out of the ordinary – it’s that it doesn’t.

Fear is all about reaction and, for a lot of things that celebrate the scary, that reaction can be pushback. In 1984, protesters organized to have Silent Night, Deadly Night pulled from most movie theaters, and Gene Siskel even accused everyone involved with the movie of trying to earn “blood money.”

“I just don’t like being scared” is an argument we’ve all heard plenty of times before against everything from horror movies to haunted hayrides. It’s not like fear is supposed to feel good.

So then why does it feel so good for other people that they seek it out?

About 5,000 commercial haunted houses (or “haunts”) operate every year across the U.S. These come in all different forms and cover all different fears for their guests, from the family friendly Oogie Boogie Bash at Disney World to the “world’s scariest haunted house,” McKamey Manor, where guests have reportedly been waterboarded, physical assaulted, and physically and psychologically tortured in plenty of other ways. And as recently as 2019, its waiting list was a massive 24,000 people long.

Are they all just out of their minds?

That may not be too far off from it, actually – but probably not in the way you think. Margee Kerr, Ph.D., studies fear professionally at the University of Pittsburgh, alongside her work with the Pittsburgh-area haunt ScareHouse. After consulting on the haunt’s design to create a peak-fear experience, Kerr had an idea: it would be the perfect place to find volunteers for her research.

In a 2019 study, her team found that people not only left ScareHouse in a better mood than they’d went in with, but that they had decreased brain activity, higher levels of feel-good hormones like endorphins, and were better able to handle stressors afterward – similar on a physical and mental level to a runner’s high or a state of peace in meditation.

Mood increases were especially significant for people saying that they’d “challenged their fears.”

“What we are finding is that by focusing on a very ‘up’ emotion, a scare response is going to help people with anxiety and rumination,” Kerr says. That big emotion of a scare essentially “gives you a second to reset and start going down a new path.”

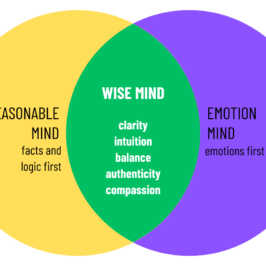

It’s just like a psychological treatment called exposure therapy.

Exposure therapy is a form of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) developed in the 1950s as a way to help people suffering from phobias, panic disorders, and anxiety disorders “break the pattern of avoidance and fear.” Someone dealing with a fear (of germs, for example) will work with their therapist to safely expose themselves to places, things, and behaviors they’ve specifically been avoiding (like touching a busy store’s card reader keypad).

In time, it can help people learn how to process uncomfortable emotions, weaken the associations they have between scary situations and bad outcomes, and even become comfortable feeling their fear. It may not mean that people feel totally comfortable in uncomfortable situations, but that they can own their feelings rather than their feelings owning them.

So it may be scary to have someone coming at you with a chainsaw – but in the safety of a controlled environment like a haunted house, it becomes less threatening and maybe even exciting.

“[T]here’s a sweet spot between too much fear and not enough fear, between predictability and unpredictability, where you feel you have a certain amount of control over the situation, but there’s still a degree of unpredictability,” researcher Mathias Clasen says.

Clasen is the Director of the Recreational Fear Lab at Denmark’s Aarhus University, where he studies why fear isn’t just a survival mechanism, like we usually think of it as, but how it can also be fun, social, and even meaningful. He even compares that “sweet spot” of fear to play, fulfilling certain needs and expectations while still leaving room for surprise and spontaneity – all while avoiding a scare-overload that can make an experience traumatic.

“We find and challenge our own limits. And we may even practice coping strategies,” Clasen says. “It does not make us fearless, but it does seem to make us better at regulating fear.”

Clasen raises a good point: for as fun as spooks and scares can be, what’s really the point of horror?

If I can be so bold as to amend Eshuis’ review of Child’s Play from before, I’d say that nightmare material actually has much, much more value than we give it credit for.

We go into a haunted house knowing that, after a few minutes, we’ll come back out. For as dark and twisted as we always think of horror as, that isn’t horror at its best. The best scares help us test ourselves, and face our fears, and walk away victorious over the things that scare us. It’s a chance to remind ourselves that we can still discover strength within ourselves and triumph against the odds, even in the face of true terror.

DISCLAIMER

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new health care regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.