If you are thinking about harming yourself or attempting suicide, tell someone who can help right away. Call 911 for emergency services, go to the nearest hospital emergency room, or call or text 988 to connect with the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. The Lifeline provides 24-hour, confidential support to anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress.

By: Maria Karolenko, LCPC

Suicide has a special stranglehold on most people. It’s often treated as “the unspeakable,” “the unthinkable,” “the unimaginable.” So is it any wonder that, for many, talking about suicide is more difficult and more complicated than almost anything else in the larger conversation around mental health?

While discussions around illnesses like depression and anxiety have moved leaps and bounds ahead of where they were just a few years ago, sometimes it can feel like the delicacy around suicide has meant that, in some ways, it’s been left behind. For those experiencing thoughts of suicide, grieving loved ones who have died by suicide, struggling to reach out to talk honestly about suicide, the hushed tones others use when even saying the word can reinforce the idea: this is a shameful thing.

There is a common belief that suicide is like toxic waste – even getting a little close to it can be dangerous. “Talk about it and things get worse.” “Reveal that that’s how someone died and things get worse.” For many people, staying as far away from any mention of it feels like the safest course of action. Research, however, suggest that things are actually a bit more complicated.

In the aftermath of Kurt Cobain’s death in 1994, suicidologists and the public at large worried that the news would inspire copycat suicides across the country. With Nirvana’s audience of mainly vulnerable young people, it seemed like the biggest rock star in the world would still hold tremendous sway over his fans even in death (especially in the famously melancholy state of Washington). But to everyone’s surprise, the rise in suicides never happened. There was actually a drop in suicides compared to the same point in 1993, while calls to suicide crisis lines drastically rose and people received the help they needed before it was too late.

While it’s difficult, even 30 years later, to say what exactly made this happen, the efforts within the Seattle community to provide support and access to mental health resources cannot be undersold.

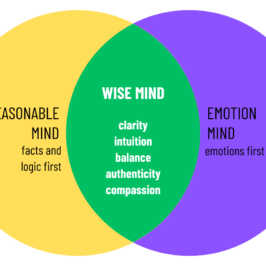

Through having conversations about this, it allows people to feel less alone and can help them “Name It to Tame It.” In my experience as a therapist, I have found that when people are about to talk out these thoughts and feelings they generally decrease – and neuroimaging research has backed this up.

As conversations increase, though, so does the chance for pushback or for people to say unhelpful or even harmful things. In the heat of emotion, some people may approach the topic with phrases like “ I would never” or “How could they do this to their family?” or “They’re going to Hell.” And while statements like these can feel true in the moment, they close off the conversation and limit the potential to learn, explore our feelings, and have a thoughtful conversation on the topic.

We can see this in the move away from judgmental language like “committed suicide,” which draws parallels to the way we talk about crimes (“committed murder,” “committed arson,” “committed an assault”). Language that reframes it as the end of a sickness removes judgement and encourages people to open up about any suicidal feelings so they may access care, rather than sit in their shame; something like “died by suicide” is much closer to the way we’d talk about breast cancer or heart disease.

But as the need rises to integrate more socially aware language into our conversations, we also need to have more concise research on the topic to help guide conversations happening on a massive scale.

Media like 13 Reasons Why and Dear Evan Hansen have started the work of disentangling the stigma around even mentioning suicide, and found large fan followings for it, but with so much work still to be done it was obvious quickly that it would come with some large and costly mistakes. 13 Reasons Why especially gained notoriety early on for its graphic on-screen depiction of a fatal suicide attempt – a scene that was eventually removed following years of strong backlash and extensive research into what responsible conversations around suicide should look and sound like.

While researchers are not sure how involved the show was, they did note a 28.9% increase in fatal suicide attempts among young people in the month after it was released – higher than any single month during the five-year period they examined. But whether it was directly responsible or coincidental timing is still not clear, reminding us just how important more research into this is.

The idea behind this is known as “suicide contagion.” Like suicidologists worried about copycats after Cobain’s death, it theorizes that “an increase in suicide and suicidal behaviors [can happen] as a result of the exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviors within one’s family, peer group, or through media reports.” When we look at the concept of contagion, the big separation is between social environment (like if a friend, neighbor, or classmate dies by suicide), news media (like coverage over the death of Cobain), and fictional television (like 13 Reasons Why).

The strongest finding in recent research is that the social contagion, having a person close to you complete suicide, is the biggest factor that may elevate someone’s risk. This is even true for people who are not directly impacted by a death, like someone who lives down the street, knows a surviving family member, or simply saw them around town.

Kimberly O’Brien, clinical social worker in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Boston Children’s Hospital, says, “After suicide, the person’s closest friends aren’t necessarily the ones at greatest risk. The kids at greatest risk are the ones who are already emotionally vulnerable and those who believe their classmate solved their problems through suicide.”

Because whether a loss is close to us or farther away, it easily digs up messy, complicated, uncomfortable feelings in people. Conversations around suicide need to occur, both for people struggling with their own mental health and for people who are not – the only question is what they should look like to help people as best as possible. It’s clear that without unlearning the lessons many of us have been taught about suicide or making room for conversations to happen in a safe space, those feelings will only continue.

O’Brien says, “Parents should not try to keep the suicide a secret from their kids. You don’t want to focus on the method of death, but don’t take away from the loss of this person by not doing or saying anything. . . The emphasis should be on suicide prevention.”

As people struggle with their own thoughts of suicide or deal with the aftereffects of someone else’s, there can be a lot of shame wrapped up in the feeling that everything’s not fine. If we don’t allow feelings like that to come out in the open, all we do is decide to bear the weight of that. All we do is decide to wait until it becomes too much to hold.

If you are thinking about harming yourself or attempting suicide, tell someone who can help right away. Call 911 for emergency services, go to the nearest hospital emergency room, or call or text 988 to connect with the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. The Lifeline provides 24-hour, confidential support to anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress.

DISCLAIMER

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new health care regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.